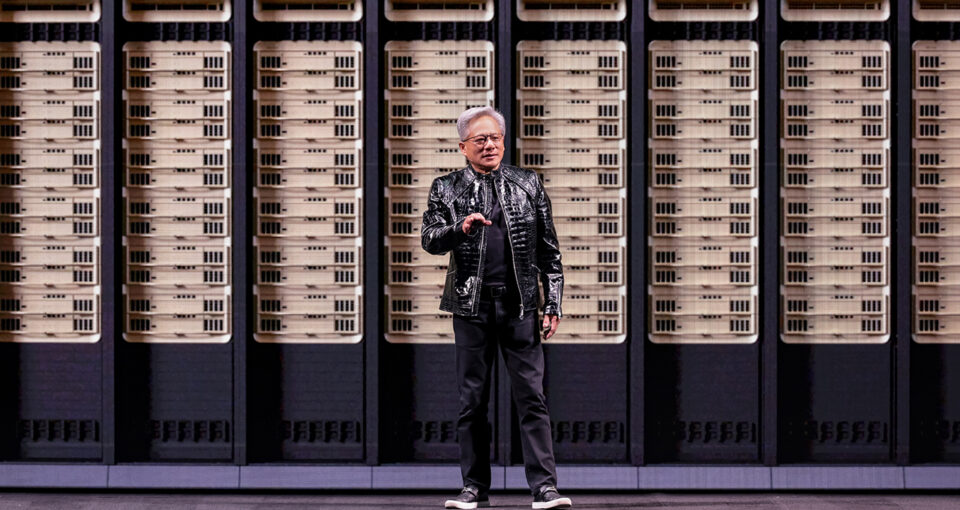

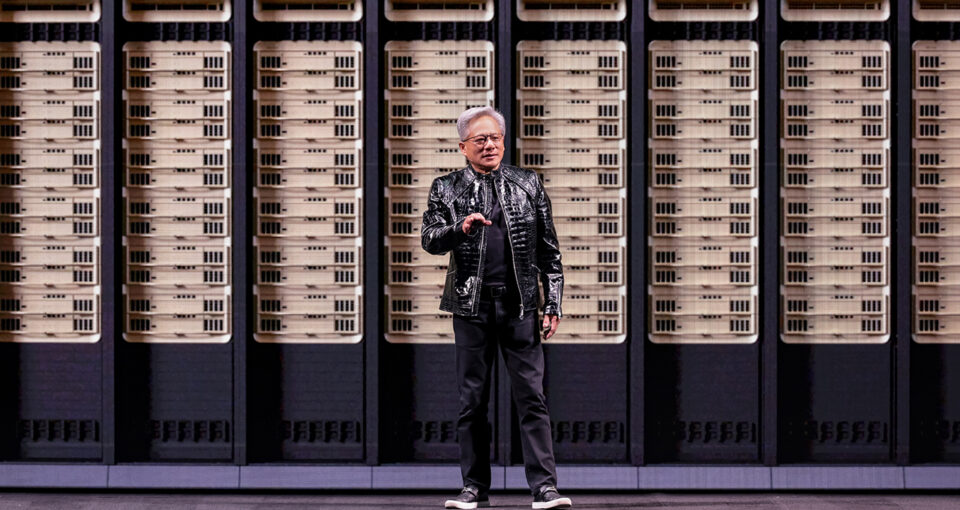

NVIDIA founder and CEO Jensen Huang took the stage at the Fontainebleau Las Vegas to open CES 2026,… Read Article

NVIDIA founder and CEO Jensen Huang took the stage at the Fontainebleau Las Vegas to open CES 2026,… Read Article

Unveiling what it describes as the most capable model series yet for professional knowledge work, OpenAI launched GPT-5.2 in December. The model was trained and deployed on NVIDIA infrastructure, including… Read Article

Celtic languages — including Cornish, Irish, Scottish Gaelic and Welsh — are the U.K.’s oldest living languages. To empower their speakers, the UK-LLM sovereign AI initiative is building an AI… Read Article

For more than a century, meteorologists have chased storms with chalkboards, equations, and now, supercomputers. But for all the progress, they still stumble over one deceptively simple ingredient: water vapor…. Read Article

Bringing together the world’s brightest minds and the latest accelerated computing technology leads to powerful breakthroughs that help tackle some of the biggest research problems. To foster such innovation, the… Read Article

AI and graphics research breakthroughs in neural rendering, 3D generation and world simulation power robotics, autonomous vehicles and content creation…. Read Article

The University of Bristol’s Isambard-AI, powered by NVIDIA Grace Hopper Superchips, delivers 21 exaflops of AI performance, making it the fastest system in the U.K. and among the most energy-efficient… Read Article

Ceramics — the humble mix of earth, fire and artistry — have been part of a global conversation for millennia. From Tang Dynasty trade routes to Renaissance palaces, from museum… Read Article

At GTC Paris — held alongside VivaTech, Europe’s largest tech event — NVIDIA founder and CEO Jensen Huang delivered a clear message: Europe isn’t just adopting AI — it’s building… Read Article