What’s a three-letter acronym for a “video-handling chip”? A GPU, of course. Who knew, though, that these parallel processing powerhouses could have a way with words, too.

Following a long string of victories for computers in other games — chess in 1997, go in 2016 and Texas hold’em poker in 2019 — a GPU-powered AI has beaten some of the world’s most competitive word nerds at the crossword puzzles that are a staple of every Sunday paper.

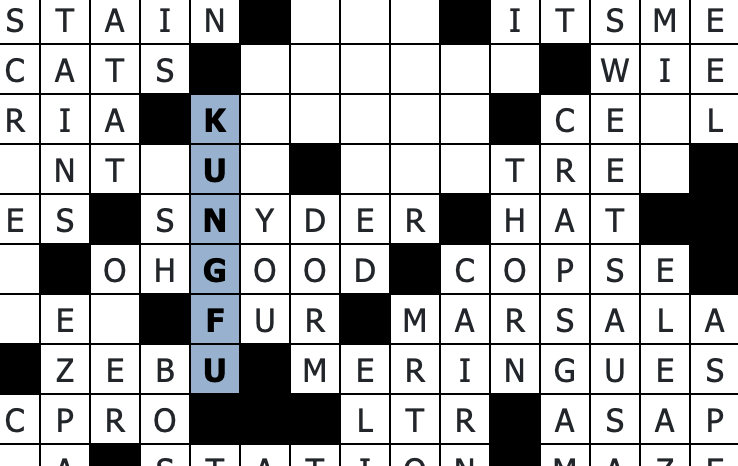

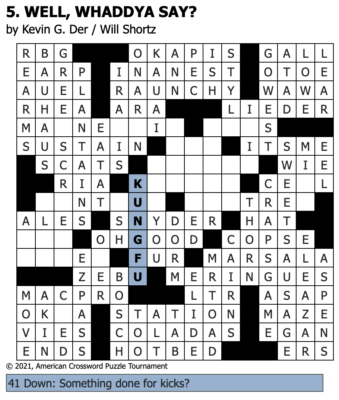

Dr.Fill, the crossword puzzle-playing AI created by Matt Ginsberg — a serial entrepreneur, pioneering AI researcher and former research professor — scored higher than any humans last month at the American Crossword Puzzle Tournament.

Dr.Fill’s performance against more than 1,300 crossword enthusiasts comes after a decade of playing alongside humans through the annual tournament.

Such games, played competitively, test the limits of how computers think and help researchers better understand how people do, Ginsberg explains. “Games are an amazing environment,” he says.

Dr.Fill’s edge? A sophisticated neural network developed by UC Berkeley’s Natural Language Processing team — trained in just days on an NVIDIA DGX-1 system and deployed on a PC equipped with a pair of NVIDIA GeForce RTX 2080 Ti GPUs — that snapped right into the system Ginsberg had been refining for years.

“Crossword fills require you to make these creative multi-hop lateral connections with language,” says Professor Dan Klein, who leads the Natural Language Processing team. “I thought it would be a good test to see how the technology we’ve created in this field would handle that kind of creative language use.”

Given that unstructured nature, it’s amazing that a computer can compete at all. And to be sure, Dr.Fill still isn’t necessarily the best, and that’s not only because the American Crossword Puzzle Tournament’s official championship is reserved only for humans.

The contest’s organizer, New York Times Puzzle Editor Will Shortz, pointed out that Dr.Fill’s biggest advantage is speed: it can fill in answers in an instant that humans have to type out. Judged solely by accuracy, however, Dr.Fill still isn’t the best, making three errors during the contest, worse than several human contestants.

Nevertheless, Dr.Fill’s performance in a challenge that, unlike more structured games such as chess or go, rely so heavily on real-world knowledge and wordplay is remarkable, Shortz concedes.

“It’s just amazing they have programmed a computer to solve crosswords — especially some of the tricky hard ones,” Shortz said.

A Way with Words

Ginsberg, who holds a Ph.D. in mathematics from the University of Oxford and has 100 technical papers, 14 patents and multiple books to his name, has been a crossword fan since he attended college 45 years ago.

But his obsession took off when he entered a tournament more than a decade ago and didn’t win.

“‘The other competitors were so much better than I was, and it annoyed me, so I thought ‘Well, I should write a program,’ so I started Dr.Fill,” Ginsberg says.

Organized by Shortz, the American Crossword Tournament is packed with people who know their way around words.

Dr.Fill made its debut at the competition in 2012. Despite high expectations, Dr.Fill only managed to place 141st out of 600 contestants. Dr.Fill never managed a top 10 finish until this year.

In part, that’s because crosswords didn’t attract the kind of richly funded efforts that took on — and eventually beat — the best humans at chess and go.

It’s also partly because crossword puzzles are unique. “In go and chess and checkers, the rules are very clear,” Ginsberg says. “Crosswords are very interesting.”

Crossword puzzles often rely on cryptic clues that require deep cultural knowledge and an extensive vocabulary, as well as the ability to find answers that best slide into each puzzle’s overlapping rows and columns.

“It’s a messy thing,” Shortz said. “It’s not purely logical like chess or even like Scrabble, where you have a word list and every word is worth so many points.”

A Winning Combination

The game-changer? Help from the Natural Language Processing team. Inspired by his efforts, the team reached out to Ginsberg a month before the competition began.

It proved to be a triumphant combination.

The Berkeley team focused on understanding each puzzle’s often gnomic clues and finding potential answers. Klein’s team of three graduate students and two undergrads took the more than 6 million examples of crossword clues and answers that Ginsberg had collected and poured them into a sophisticated neural network.

Ginsberg’s software, refined over many years, then handled the task of ranking all the answers that fit the confines of each puzzle’s grid and fitting them in with overlapping letters from other answers — a classic constraint satisfaction problem.

While their systems relied on very different techniques, they both spoke the common language of probabilities. As a result, they snapped together almost perfectly.

“We quickly realized that we had very complementary pieces of the puzzle,” Klein said.

Together, their models parallel some of the ways people think, Klein says. Humans make decisions by either remembering what worked in the past or using a model to simulate of what might work in the future.

“I get excited when I see systems that do some of both,” Klein said.

The result of combining both approaches: Dr.Fill played almost perfectly.

The AI made just three errors during the tournament. Its biggest edge, however, was speed. It dispatched most of the competition’s puzzles in under a minute.

AI Supremacy Anything But Assured

But since, unlike chess or go, crossword puzzles are ever-changing, another such showing isn’t guaranteed.

“It’s very likely that the constructors will throw some curveballs,” Shortz said.

Ginsberg says he’s already working to improve Dr.Fill. “We’ll see who makes more progress.”

The result may be out to be even more engaging crossword puzzles than ever.

“It turns out that the things that are going to stump a computer are really creative,” Klein said.