Now Live: The World’s Most Powerful AI Factory for Pharmaceutical Discovery and Development

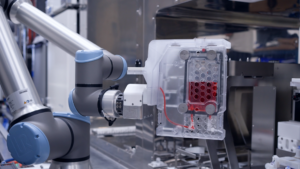

Lilly this week launched the most powerful AI factory wholly owned and operated by a pharmaceutical company to help its teams make meaningful medical advancements faster, more accurately and at...